Vladimir Putin’s 17 years in power: the scorecard

Mr. Putin can’t seem to get a break in the western

media. I watched his recent interview with CBS’s Megyn Kelly with her tiresome,

boring questions like, “did Russia interfere in our election,” “did your

ambassador meet with Trump’s election officials,” “isn’t it true that

you’re a corrupt murderous thug,” etc. Only in response to Kelly’s

last question did Mr. Putin get to name a handful of his achievements in

Russia. But someone ought to better prepare his talking points on this score.

The below excerpt from my upcoming book summarizes how Russia has changed

during the 17 years since Mr. Putin has been at helm.

Beware of the false prophets, who come to you in

sheep’s clothing, but inwardly are ravenous wolves. You will know them

by their fruits. Grapes are not gathered from thorn bushes nor figs

from thistles, are they? So every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree

bears bad fruit

Matthew 7:16

On 26th July 2014 British magazine

“The Economist” published an article titled “A web of lies,” opening with the

following two sentences: “In 1991, when Soviet Communism collapsed, it

seemed as if the Russian people might at last have the chance to become

citizens of a normal Western democracy. Vladimir Putin’s disastrous

contribution to Russia’s history has been to set his country on a different

path.” Well, we have already seen how Russia fared in the 1990s after

Soviet communism collapsed. For some reason, the bright minds at The Economist

thought this path was so promising, it was a real shame – a disaster, no less –

that Vladimir Putin took Russia on a different one. Let’s take a closer look,

shall we, at Mr. Putin’s “disastrous contribution.”

To start with, Putin played the pivotal role in

keeping the country from disintegrating. When he came to power, Russia’s

regional governors were writing their own laws, disregarded presidential

instructions and were not even returning their republics’ tax receipts to the

Federation’s purse. Mikhail Gorbachev stated that Putin “saved Russia from

the beginning of a collapse. A lot of the regions did not recognize our

constitution.” [1] But this historical feat was only

the starting point of the subsequent renaissance of the nation. Its economy

returned to growth and became more vibrant and diverse than it had been perhaps

since the reforms of Pyotr Stolypin of the early 1900s.

Economic reforms

In 2000, Russia was one of the most corrupt countries

in the world. Without instituting draconian purges Putin took on the oligarchs

and steadily curtailed their power, gradually returning Russia to the rule of

law. By 2016 his government reduced corruption to

about the same level as that of the United States. That was the empirical

result of the annual study on corruption published in 2016 by Ernst & Young.[2] The global auditing consultancy

asked respondents around the world whether in their experience, corruption is

widespread in the business sector. Their survey, which was conducted in 2014,

indicated that only 34% of their Russian respondents thought so, the same

proportion as in the United States, and below the world average of 39%. Things

have probably improved further since then as Vladimir Putin stepped up a

high-profile anti-corruption campaign that led to investigations and

prosecution of a number of high level politicians around Russia. Even highly

ranked members of Putin’s own political party were not spared.[3] The unmistakable message of such

campaigns was that corruption would not be tolerated and that it would be

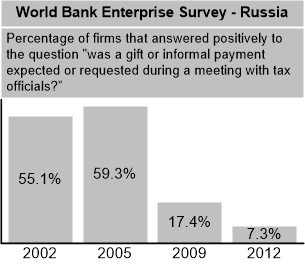

aggressively investigated and prosecuted. Some of the best evidence that

Putin’s various anti-corruption measures have had effect can be found in World

Bank’s Enterprise Surveys which ask businessmen the question, “was a gift or

informal payment expected or requested during a meeting with tax officials?”

In 2005, nearly 60% of respondents answered affirmatively. By 2009 this number

was 17.4% and by 2012 it had dropped to only 7.3%.

Putin’s government also made impressive advances in

making it easier for entrepreneurs and small businesses to set up shop, raise

capital and operate in Russia. According to World Bank’s annual “Doing

Business” report, which ranks 190 world economies on a set of attributes such

as the ease of starting a business, obtaining construction permits, obtaining

electricity, raising credit, and enforcing contracts. On all the metrics

combined, Russia managed to climb from 124th place in the world

in 2012 to 40th in 2017.[4]Thus, within only five years, Russia had

vaulted an impressive 84 positions in World Bank’s ranking. This was not a

random achievement but the result of President Putin’s explicit 2012 directive

that by 2018 Russia should be among the top 20 nations in the world for ease of

doing business.

One of the strategically important sectors where

Russia has made striking progress is its agricultural industry. After the

disastrous 1990s when she found herself dependent on food imports, Russia again

became self-sufficient in food production and a net food exporter. By 2014,

Russian exports of agricultural products reached nearly $20 billion, almost a

full third of her revenues from oil and gas exports. Not only is Russia now

producing abundant food for its own needs, the government is explicitly

favoring production of healthy foods, a strategy which includes a ban on the

cultivation of genetically modified (GMO) crops, introduced by the State Duma

in February of 2014. According to official Russian statistics, the share of GMO

foods sold in Russia declined from 12% in 2004 to just 0.1% by 2014.

These and many other constructive reforms have had a

very substantial impact on Russia’s economic aggregates as the following

examples show:

- Between 1999 and

2013, Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP) leaped nearly 12-fold from

$1,330 per capita to more than $15,560 in 2013, outpacing even China’s

remarkable economic growth.

- Russia reduced its

debt as a percentage of GDP by over 90%, from 144% in 1998 to less than

14% in 2015!

- Gross national

income per capita rose from $1,710 in 2000 to $14,810 in 2013.

- Unemployment fell

from 13% in 1999 to below 5% in 2014. Among the working population (those

aged 15-64), 69% have a paid job (74% of men).

- Only 0.2% of

Russians work very long hours, compared to 13% OECD average

- Poverty rate fell

from 40% in the 1990s to 12.5% in 2013 – better than U.S. or German

poverty rates (15.6% and 15.7%, respectively)

- Average monthly

income rose from around 1,500 rubles in 1999 to nearly 30,000 rubles in

2013.

- Average monthly

pensions rose from less than 500 rubles to 10,000 rubles.

Social and demographic improvements

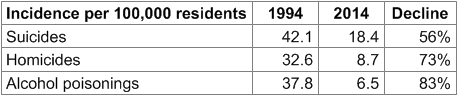

Putin’s economic reforms included also a more

equitable distribution of wealth. As hopelessness faded and standard of living

improved, Russian society started to heal: suicides, homicides, and alcohol

poisonings declined dramatically. Over the twenty-year period between 1994 and

2014, suicides declined by 56%, homicide rate by 73%, and alcohol poisonings by

83%!

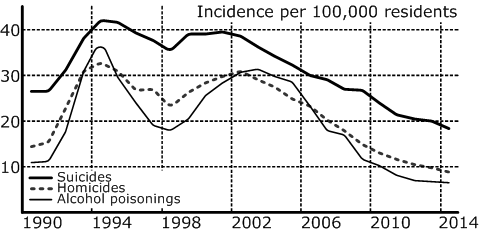

The chart below shows the evolution of these

improvements over time:

As we can see, these misery statistics rapidly

deteriorated with the introduction of shock therapy in 1992, but the trend

sharply reversed soon after Putin took charge. By 2014, these figures reached

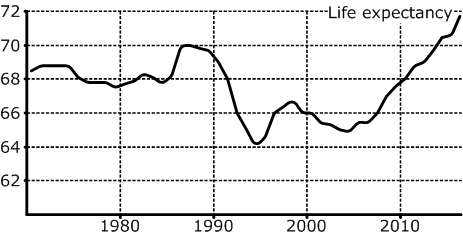

their lowest values since even before 1992. Along with these improvements, the

nation’s demographic trends also experienced a dramatic turnaround. Russian

life expectancy, which sunk to an average of barely 64 years (57 for men), rose

steadily from the early 2000s to reach almost 72 in 2016, the highest it has

ever been in Russia’s history.

Looking at the way life expectancy in Russia changed

over time, we see again that it had collapsed in the early 1990s but the trend

turned around sharply under Vladimir Putin’s leadership of the country.

Similarly fertility rate, which dropped to 1.16 babies per woman in 1999,

increased by almost 50% to 1.7 babies by 2012, comparing favorably to European

Union’s average of 1.55 babies per woman of childbearing age. Abortions

declined 88% from a harrowing 250% of live births in 1993 to 31% in 2013.

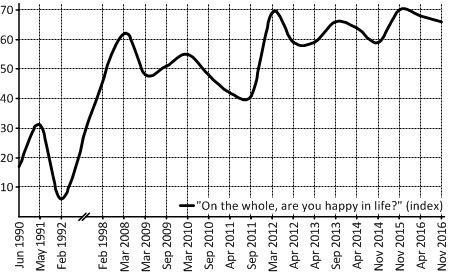

Not only are Russians living longer than ever before

and enjoying much better quality of life, they also feel freer and

happier. In 2014, Gallup Analytics reported that 65% of Russians, more

than ever before, answered “Yes” when asked, “are you satisfied … with your

freedom to choose what you do with your life?” Meanwhile, Russia’s

happiness index rose more than tenfold, from 6 in 1992 to 70 in 2015. Happiness

index, compiled by VCIOM[5] adds the proportion of the

respondents reporting that they feel decidedly happy or generally happy and

deducts those that report feeling generally unhappy or decidedly unhappy.

The next chart further corroborates the idea that

under Putin’s leadership, Russia has been developing as a sane and prosperous

society, not only for the benefit of a narrow ruling class and at everyone

else’s expense, but for the vast majority of ordinary Russians.

By 2014, the great majority of Russians felt satisfied

with their lives and believed that things in Russia were moving in the right

direction. These figures only tapered off after the 2014 western-sponsored coup

in Ukraine and the subsequent economic sanctions imposed on Russia. At the same

time, the price of oil – still one of Russia’s largest export – collapsed from

over $100 per barrel to under $40. Economic sanctions and the oil price

collapse triggered a significant crisis in Russia’s economy. However, in spite

of the continuing sanctions regime imposed on the country, its economy started

improving again in 2016, thanks to its diverse industrial base that includes a

developed commercial and consumer automotive industry, advanced aircraft and

helicopter construction based largely on domestic technologies, world’s leading

aerospace industry building satellites and top class rocket engines, and

advanced industries in pharmaceutical, food processing, optical device, machine

tools, tractors, software and numerous other branches. Indeed, Russia is far

from being just the “Nigeria with missiles,” or a “gas station with an army,”

as many western leaders like to characterize it.

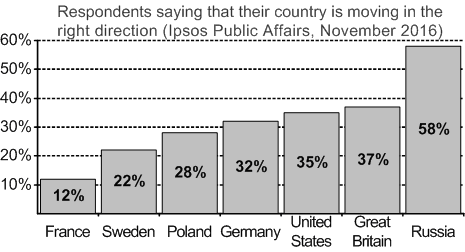

Insofar as a population’s sentiment is a valid measure

of its leadership’s performance, Russia’s development under Vladimir Putin

stands in sharp contrast with the weak performance of most other developed

nations, including those that most vehemently criticize Russia and its

president. According to polls conducted by Ipsos Public Affairs in 25 different

countries in November 2016 and published by the World Economic Forum, almost

two thirds of the people in the world believed that their countries were moving

in the wrong direction. The leading western nations scored just as badly, while

some among them did flat out dismally.

Evidently, Russians feel much better about the way

their nation is shaping up than do constituents of many western nations[6] whose sanctimonious leaders like to

lecture their Russian counterparts about prosperity, freedom, democracy and

other exalted values they purport to cherish.[7] It may thus only surprise the most

credulous consumers of western propaganda that a high proportion of Russian

people trust Vladimir Putin and approve his job performance. In the early 2017,

Putin’s job approval stood between 80% and 90% and has averaged 74% over the

eleven years from 2006. During this period, no western leader has come even

close to measuring up with Vladimir Putin.

Over the years, I’ve heard depressingly many

intellectuals attempt to dismiss Putin’s achievements and Russian people’s

contentment as the product of Russian government propaganda. Putin the

autocrat, you see, keeps such tight control over the media that he can deceive

his people into believing that things in the country are much better than they

really are. But the idea that government propaganda can influence public

opinion in this way is just silly. If the majority of people thought their

lives were miserable, state propaganda could not persuade them that everything

is great. On the contrary, most people would conclude that the media is

deceiving them and might feel even less positive about things as a result.[8] It is sillier still to think that

western intellectuals should have a better appreciation of what it is like to

live in Russia than the Russian people themselves. Rather than buying the truth

from their media, such intellectuals would do well to take a trip and visit

Russia, speak to ordinary people there, and reach their own conclusions. My own

travels in Russia, as well as reports from other visitors largely agree with

the positive picture that emerges from the statistics we’ve just examined.

No comments:

Post a Comment